The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) remains one of the most sophisticated media production machines on the planet. Its ubiquitous advertising filters into every aspect of our lives, from public schools to product placement in the lucrative gaming industry to traditional online ads.

In 2007 alone, according to a Rand Corp. study, the total recruiting budget for the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps exceeded $3.2 billion. Rand Corp. analysts also deemed those investments as successful as measured by recruitment, even during two ongoing wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Events with military personnel always feature sophisticated press and social media coverage. One of the more nuanced and I think effective messages I have seen from the DoD is how the military is not just about defense, but about a more deeply and morally resonant “good.” The U.S. Navy’s very slick videos call the branch a “a global force for good,” and show Navy SEALs in action carrying that message.

Helping to prop up that messaging is the country’s long-standing integration of public health services into the DoD and overall military readiness. The military is successfully integrating public health activities, and it is branding these as part of its global efforts, including on the new battlefield in Africa.

Through contracting opportunities that support these efforts, many U.S. based firms who specialize in development and traditional public health activities are actively supporting these initiatives, in order to monetize their own business models.

Chasing contracts serving two masters: public health and defense

I recently stumbled on a job posted on the American Public Health Association (APHA) LinkedIn page by a company called the QED Group, LLC. The position was similar to ones I see posted on their job site now, for work on a “monitoring and evaluation” project in Africa.

This is one of many government-contracting agencies that chase hundreds of millions of contracts with U.S. government agencies and the major public health funders like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

In this case, the company was specifically targeting those in the public health community, who are entering the field or currently have positions with backgrounds in public health, economics, science, and health. The 15-year-old company itself actually began as a so-called 8(a) contractor, which means it could win no-bid and lucrative government contracts that are now the center of an ongoing and intense controversy over government waste. (These companies were created by the late Alaska Sen. Ted Stevens, who created the provision to steer billions in government contracting to Alaska Native owned firms that partner with companies like Halliburton and the Blackwater overseas and in the United States.)

Today, QED Group, LLC claims “it is full-service international consulting firm committed to solving complex global challenges through innovative solutions” by providing clients “with best-value services so they increase their efficiency, learning capacity, and accountability to the public in an ever more complex and interconnected world.” It lists standard international development and public health contract areas of health, economic growth, and democracy and governance.

QED Group is not the only multi-purpose public health and development agency chasing military and global health contracts in Africa. Another health contracting company called PPD boasts of its “long history of supporting the National Institutes of Health, the nation’s foremost medical research agency,” and that it was “awarded a large contract by the U.S. Army.” It claims its is also a “preferred provider to a consortium of 14 global health Product Development Partners (PDPs), funded in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.”

As a public health professional, QED Group looks like a great company to join. However, if one scratches deeper, one learns that this company also uses its public health competencies with the U.S. military, which is spearheaded in Africa by U.S. Africa Command, or AFRICOM. This raises larger questions of the conflicting ethics of both promoting human health and public health and also serving the U.S. Department of Defense, whose primary mission is to “deter war and to protect the security of our country.”

AFRICOM’s emerging role flexing U.S. power in Africa

AFRICOM’s demonstration of “hard power” is well-documented through its use of lethal firepower in Africa. AFRICOM is reportedly building a drone base in Niger and is expanding an already busy airfield at a Horn of Africa base in the tiny coastal nation of Djibouti. On Oct. 29, 2013, a U.S. drone strike took out an explosives expert with the al-Qaida-linked al-Shabaab terrorist group in Somalia, which had led a deadly assault at a Kenyan shopping center earlier that month.

One blog critical of the United States’ foreign policy, Law in Action, reports that the AFRICOM is involved in the A to Z of Africa. “They’re involved in Algeria and Angola, Benin and Botswana, Burkina Faso and Burundi, Cameroon and the Cape Verde Islands. And that’s just the ABCs of the situation. Skip to the end of the alphabet and the story remains the same: Senegal and the Seychelles, Togo and Tunisia, Uganda and Zambia. From north to south, east to west, the Horn of Africa to the Sahel, the heart of the continent to the islands off its coasts, the U.S. military is at work.”

U.S. efforts in Africa require health, public health, and development experts. As it turns out the company, QED Group, won a USAID contract examining U.S. efforts promoting “counter-extremism” programs in the Sahel. That study evaluated work using AFRICOM-commissioned surveys, all designed to promote U.S. national security interests in the unstable area.

The area is deeply divided between Christians and Moslems. It is also home to one of the largest al-Qaida based insurgencies known as al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, which has similar violent aspirations as the ultra-violent Boko Haram Islamic militant movement of violence-wracked northern Nigeria. Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb military seized control of Northern Mali in 2012, which ended when U.S.-supported French military forces invaded the country and routed the Islamic extremists in January 2013.

Public health’s historic role with U.S. defense and national security

“Hard power” and “soft power” are tightly intertwined in U.S. overseas efforts, where health and public health personnel support U.S. interests. This is true in Afghanistan and is certainly true in North Africa. This particular QED-led program used the traditional public health method of a program evaluation of an antiterrorism program to see if a USAID program was changing views in Mali, Niger and Chad—all extremely poor countries that are at the heart of a larger struggle between Islamists and the West.

That research methods used in public health–and which I have used to focus on health equity issues in Seattle–can be used equally well by U.S. development agencies to advance a national security agenda is not itself surprising.

However, faculty certainly did not make that case where I studied public health (the University of Washington School of Public Health). I think courses should be offered on public health’s role in national defense and international security activities, because it is nearly inevitable public health work will overlap with some form of security interests for many public health professionals, whether they want to accept this or not.

Public health in the United States began as a part of the U.S. armed services, as far back as the late 1700s. It was formalized with the military title of U.S. Surgeon General in 1870. To this day those who enter the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps wear military uniforms and hold military ranks.

A good friend of mine who spent two decades in the Indian Health Service, one of seven branches in the corps, retired a colonel, or “full bird.” He always experienced bemusement when much larger and far tougher service personnel had to salute him when he showed his ID as he entered Alaska’s Joint Base Elmendorf Fort Richardson looking often like a fashion-challenged bum in his minivan (he frequently had to see patients on base, and was doing his job well).

The U.S. Army’s Public Health Command was launched in WWII, and it remains active today. One of its largest centers is Madigan Army Medical Center at Joint Base Lewis McChord, in Pierce County, Washington. Public Health activities are central to the success of the U.S. Armed Services, who promote population-based measures and recommendations outlined by HealthyPeople 2020 to have a healthy fighting force.

AFRICOM charts likely path for the future integration of public health and defense

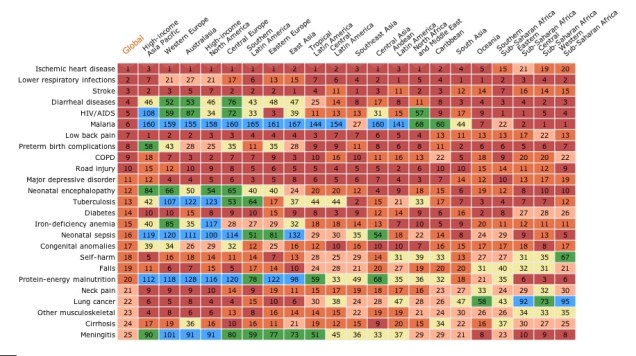

Today, the U.S. military continues to use the “soft power” of international public health to advance its geopolitical interests in North Africa. In April 2013, for example, AFRICOM hosted an international malaria partnership conference in Accra, Ghana, with malaria experts and senior medical personnel from eight West African nations to share best practices to address the major public health posed by malaria.

At last count, the disease took an estimated 660,000 lives annually, mostly among African children.

At the event, Navy Capt. (Dr.) David K. Weiss, command surgeon for AFRICOM, said: “We are excited about partnering with the eight African nations who are participating. We’ll share best practices about how to treat malaria, which adversely impacts all of our forces in West Africa. This is a great opportunity for all of us, and I truly believe that we are stronger together as partners.”

I have reported on this blog before how AFRICOM and the United States will increasingly use global health as a bridge to advance the U.S. agenda in Africa. And global health and public health professionals will remain front and center in those activities, outside of the far messier and controversial use of drone strikes.

It is likely this soft and hard power mission will continue for years to come. Subcontractors like QED Group will likely continue chasing contracts with USAID related to terror threats. Global health experts will meet in another African capital to discuss major diseases afflicting African nations at AFRICOM-hosted events. And drones will continue flying lethal missions over lawless areas like Somalia and the Sahel, launching missiles at suspected terrorist targets.