As the year 2017 comes to a close, millions of American adoptees are no closer to receiving equal treatment under U.S. laws than they were decades earlier. In 1975, the United Kingdom long moved on from this issue, giving all adoptees full access to their records once they turned 18. In fact, the issue of adoptee equal rights is not even a concern in many developed nations. Not so in the United States, the country with the greatest number of adoptees than any developed country in the world.

From a strategic perspective, most U.S. adoptees have not organized cohesively or embraced successful strategies that have altered this battlefield. This includes the all-critical inner battle of the mind that must occur first before any change and tactical advance occurs on the messy, fluid field of combat in the real world. I will focus mostly on this critical aspect of adoptee rights work in this essay, while also addressing the national scene.

Most of us know from our own experiences we can’t change the outer world without changing our inner world. I believe it is time to reset the chessboard and start anew, starting first with each individual adoptee. It is way past due for adoptees to show more backbone and grit, beginning in their own house.

Project Strength, Not Vulnerability: Today, far too many adoptees celebrate a losing attitude, portraying themselves as “trauma victims.” They confess to being desperate, needy, unhappy adults who are incapable of mastering their emotions and managing inner conflict. While there is clear and strong public health evidence on long-term health impacts of early childhood and prenatal experiences, adoptee-led trauma branding ultimately undermines adoptee rights as a larger political cause. (I write this as an adoptee born as a near-low-birth-weight infant, who needed emergency hospital care during my first two weeks of life.) So long as adoptees identify themselves as defeated souls and do not project a public image as standard bearers of centuries-old struggles for basic human rights, they will never win anything and remain captives of their own cages. Unfortunately, those who embrace a weak public image will define adoptees’ public perception and the larger national story defining adoptees and their collective national experience. As long as this losing mentality prevails, all adoptees will be held back.

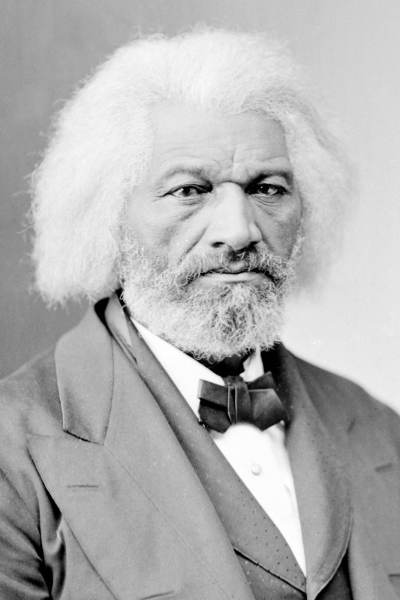

Learn from the Masters and Apply that Wisdom: Many adoptees in the United States can sharpen their focus by reading any book of their choosing that motivates them to understand conflict and struggles. Take abolitionist Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave and anti-slavery crusader and author of several books on his slavery experience. Douglass learned as a young man in captivity that his freedom came first through mental defiance and firm resolve, not in his circumstance, which he later overcame. Douglass wrote: “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them, and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.”

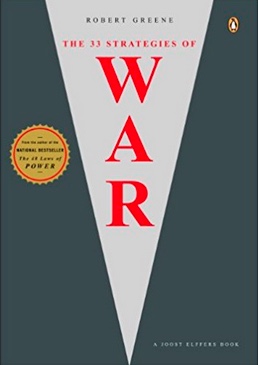

Any biography of any accomplished person will show they all had conflict and controlled their fate by first winning their internal battles. They mastered their thinking and then launched their external crusades—many more brutal and unfair than the minefield of adoptee discrimination and adoption law. For adoptees needing inspiration, I recommend the author Robert Greene, author of The 48 Laws of Power, Mastery, The 33 Strategies of War, and more. His treatise on war offers a cool, hard look at human conflict and offers wisdom demonstrated by historic greats from Sun Tzu to Napoleon Bonaparte to Muhammad Ali. He provides a set of ideas how to grab victory from whatever conflict and foes you face.

Any biography of any accomplished person will show they all had conflict and controlled their fate by first winning their internal battles. They mastered their thinking and then launched their external crusades—many more brutal and unfair than the minefield of adoptee discrimination and adoption law. For adoptees needing inspiration, I recommend the author Robert Greene, author of The 48 Laws of Power, Mastery, The 33 Strategies of War, and more. His treatise on war offers a cool, hard look at human conflict and offers wisdom demonstrated by historic greats from Sun Tzu to Napoleon Bonaparte to Muhammad Ali. He provides a set of ideas how to grab victory from whatever conflict and foes you face.

Here are a few of the concepts from Greene that I think adoptees should consider as they choose how they want to live their lives and then change the world around them.

Have a Grand Strategic Vision: Today, no grand vision unifies the adoptee rights movement—a situation that must be remedied. It is also a movement without a clearly defined national leader, unlike historic predecessors like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, ACT UP, or the Human Rights Campaign. The closest concept unifying adoptee rights is the call by many for human rights and equal rights, recognized in statute, as those laws apply to persons who were placed for adoption. This includes giving all adoptees unfettered and full access to original birth records, without any exception. Many adoptees lack a personal vision too, preventing them from achieving individual success in their fight for their rights and records. This too must be changed, but by each individual adoptee, and in their own way. Only the individual has the power to make that change.

In the United States, adoption law is controlled at the state level. Here proponents of adoption and laws ensuring adoption secrecy, such as pro-adoption, anti-adoptee rights groups like the National Council for Adoption, have maximized a divide-and-conquer strategy that prevents adoptees from mounting a national campaign. Advocacy today focuses mostly on battles in state legislatures over bills to change adoptees’ access to birth records. These fights may bring in up to three or nearly four dozen local and national groups, including longtime groups like Bastard Nation, newer upstarts like the Adoptee Rights Law Center, and state-level groups like California Open. Most adoptees are not involved in these battles as they try to find their own records or families. However, all adoptees are connected to this national debate and need the same overarching strategic approach that is needed nationally.

Ultimately not having a clear end game and objectives will prevent many adoptees from engaging fully in what will be a protracted, long campaign. That can translate to lifelong failure. Greene’s synopsis of the critical role of grand strategy should be a wake up call to all adoptee rights advocates, including those who have to advocate for themselves: “What have distinguished all history’s grand strategists and can distinguish you, too, are specific, detailed, focused goals. Contemplate them day in and day out and imagine how it will feel to reach them and what reaching them will look like. By a psychological law peculiar to humans, clearly visualizing them this way will turn into a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Learn from Defeat: Every person in life suffers setbacks. Adoptees who seek their records and identity, unlike nonadoptees, are beset by obstacles imposed by hostile public health bureaucracies, harmful propaganda from the massive pro-adoption and Christian pro-family industry, media stereotypes that frame adoptees as damaged goods or ungrateful bastards, family members, friends, and especially discriminatory laws rooted in historic prejudice against illegitimately born people. Every single defeat represents a learning opportunity if you have an open, flexible mind that can take these setbacks and inform your future efforts. As Greene notes, “Victory and defeat are what you make of them; it is how you deal with them that matters.”

Define your Opponents and Expose Them and Their Weaknesses: Greene’s 33 Strategies of War highlights countless historic examples how combatants overcome their enemies by attacking the weakest link in any chain. He calls this “hit them where it hurts.” Frequently this means exposing individuals who make decisions and holding them accountable to the public. Famous social activist Saul Alinsky, author of Rules for Radicals,” called this “picking the target.” “Don’t try to attack abstract corporations or bureaucracies,” he wrote. “Identify a responsible individual. Ignore attempts to shift or spread the blame.” For adoptee rights activists, this means putting a face on those who say “no,” rather than succumbing like sheep to the nameless bureaucrats who operate in secret and hide behind the façade of laws and “process.”

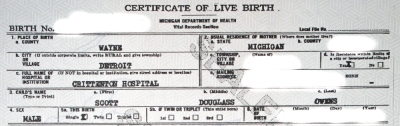

In my case, I identified every Michigan official in the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services involved in trying to withhold my birth certificate illegally, such as State Registrar Glenn Copeland. I published their emails about my birth record petition on my websites, revealing how public officials discussed adoptees seeking records that should have been released decades earlier.

Some groups, like Bastard Nation, do call out by name all of the foes and friends of adoptee rights, which others should learn from. My question to the larger adoptee community is this: Why aren’t all adoptee rights activists embracing one of the best tools of a free press, shining light on wrongdoing, to expose the harmful workings of public officials in their treatment of adoptees? This is a proven strategy and one rooted in the American free press tradition. It’s yours to use.

Become a Fighter, Not a Victim: Anyone who perceives himself or herself as crushed by circumstance will never muster the courage or vision to become an advocate or warrior for change, particularly against an old, large, and entrenched system like U.S. adoption. As Greene notes, “Control is an issue in all relationships. It is human nature to abhor feelings of helplessness and to strive for power. … Your task as a strategist is twofold: First, recognize the struggle for control in all aspects of life, and never be taken in by those who claim they are not interested in control.” Make no mistake, adoption secrecy is firmly rooted in states and their bureaucracies exerting power over a mostly unorganized group. Saying you are weak and projecting that image gives those in control greater power over you and all other adoptees. Remember Frederick Douglass’ admonishment that the “limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.”

Become a Fighter, Not a Victim: Anyone who perceives himself or herself as crushed by circumstance will never muster the courage or vision to become an advocate or warrior for change, particularly against an old, large, and entrenched system like U.S. adoption. As Greene notes, “Control is an issue in all relationships. It is human nature to abhor feelings of helplessness and to strive for power. … Your task as a strategist is twofold: First, recognize the struggle for control in all aspects of life, and never be taken in by those who claim they are not interested in control.” Make no mistake, adoption secrecy is firmly rooted in states and their bureaucracies exerting power over a mostly unorganized group. Saying you are weak and projecting that image gives those in control greater power over you and all other adoptees. Remember Frederick Douglass’ admonishment that the “limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.”

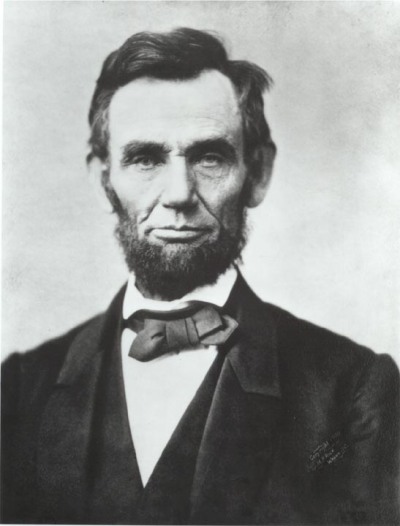

Therefore adoptees should see themselves as members of a powerful group, who have been forged through adversity and opposition, who are connected to historic heroes who fought for rights on behalf of those denied their rights. Nearly every great civilization has a story of those who have been wronged, but who changed the course of events by becoming the strong. In Scotland, the hero was Robert the Bruce, who defeated the English. In ancient Rome it was Spartacus and the revolting slaves, whose legacy survived millennia after their defeat. In the American South, it was the Civil Rights activists and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference led by Dr. Martin Luther King, who challenged the power of the Southern states and Jim Crow laws and won major legislative change nationwide with the passage of two landmark civil rights measures. Find the hero and movements that resonate with you and embrace their power.

Define The Battlefield: In his summary of war strategies, Greene writes, “To have the power that only strategy can bring, you must be able to elevate yourself above the battlefield, to focus on your long-term objectives, to craft an entire campaign, to get out of the reactive mode that so many battles in life lock you into. Keeping your overall goals in mind, it becomes much easier to decide when to fight and when to walk away.” Today, much of U.S. adoptee rights advocacy is stuck in complicated, state-level legislative battles over often regressive state legislation. Most recently, state lawmakers in New York and Florida have introduced legislation that has consumed adoptee rights advocates. In Hawaii in 2016, adoptee rights champions did define the battlefield and reclaimed their rights by passing a law granting all adoptees who are adults over 18 access to their records. In other cases, like New Jersey, a law was signed in 2014 and implemented in 2016 that created a class of adoptees denied forever their human right to know their ancestry because of a so-called “veto.”

Missing in this tactical coverage is how the adoptee rights struggle should be told nationally, outside of the typical media obsession over adoption reunion stories (what some adoptees call “reunion porn”). That space has been seized in the post-World War II decades by the pro-life, Christian, and fundamentalist community who have forged a national story about adoption as a selfless act promoting god’s will and a system that shows the benevolence of loving adoptive families. Adoptee strategists will need to counter the adoption industry’s national story by focusing on adoptee rights as human rights and as something as American as the First Amendment. Some advocates are doing this. More needs to be done. Frontline adoptee activists need to fight off any pretender group that claims that space. As Green states, “War demands the utmost in realism, seeing things as they are.”

Know Your Enemies: Greene correctly states that no one in history ever won anything without first identifying those who opposed them. “Life is endless battle and conflict, and you cannot fight effectively unless you identify your enemies,” writes Greene. This maxim applies to the struggle for adoptees. Bastard Nation did that well already, publishing a list of many dogged and well-financed foes of adoptee rights (“Know Thine Enemies”). In knowing who they face, adoptees are better able to find allies, collaborators, and even possible swing groups who may pivot if the messages of equality, human rights, and justice override the powerful and slippery propaganda of the well-funded, Christian-leaning, anti-abortion, and pro-adoption advocates like the National Council for Adoption.

Adoptee rights strategists must familiarize themselves with overt anti-adoptee rights groups and their methods to develop a winning strategy. Greene correctly summarizes what hundreds of other historic strategists who have made history have long noted: “Do not be naïve: with some enemies there can be no compromise, no middle ground.” For that reason, adoptee rights groups will face continued setbacks if they also fail to recognize false advocates (the “Benedict bastards”) and those who divide and conquer among adoptees themselves. Adoptees need to use this real politik litmus test for groups who lack a clear vision for full equality, including state-level charlatan groups who claim to support adoptee rights, but promote harmful laws that deny all equal rights.

Launch a Revolution of Thinking: As Greene notes, all people face battles, hourly and daily. “But the greatest battle of all is with yourself—your weakness, your emotions, your lack of resolution in seeing things through to the end,” writes Greene. “Instead of repressing your doubts and fears, you must face the down, do battle with them.” Above all, success comes after you remove distracting emotion from critical thinking. This is a tall task for any adoptee, who often and rightly feels outrage and injustice at being denied their original names, equal legal rights, medical history, and equality. What results is an explosive outrage. This feeling has frequently served as great motivator, and even a catalyst for historic change.

To overcome your adversaries and the underlying legal injustice, you cannot afford the luxury of wallowing in your emotional state or turmoil when you map your long-term strategy for victory. You need to master your situation, turn your defeats into wisdom that inform your future actions, and embrace actions that achieve clear victories and not repeated losses. This can take years. You will get nowhere unless you define where your campaign will end and what you fight for. A campaign devoid of justice and focused on piecemeal objectives—the approach of some so-called adoptee rights advocates—is not a coherent, visionary strategy. It is a losing campaign before the battle begins.

Fighting a long game and knowing your actions are just and that laws are wrong can help carry you through the months and years of defeat. But ultimately winning the battle in one’s mind is your greatest key to victory. As the great Chinese strategist Sun-Tzu wrote nearly 2,500 years ago: “Victorious warriors win first and then go to war, while defeated warriors go to war first, and then seek to win.”

[Author note: On June 10, 2018, I updated this essay, removing references to the now closed Donaldson Adoption Institute, and the American Adoption Conference (AAC). Regarding the AAC, the group this spring announced a very clear policy position supporting the right of adoptees to be treated equally by law, which signalled to me the group is commited to genuine legal reform and thus the activities to achieve that in the years to come.]