The business press and the communications teams in the private sector work hard to show that innovation mingles in the air like oxygen at successful businesses. The theory goes, innovation breeds success, which creates profits, which spurs new products and services and wealth, which of course is good for the economy and thus all of us.

Forbes, for instance, showcases business innovators, like Starbucks and Amazon, by highlighting metrics that the magazine considers to be markers of innovation. According to the Forbes’ Sept. 2, 2013, piece on innovation, Amazon’s CEO Jeff Bezos says he looks for traits in innovators in his company and allows for innovation to occur three ways:

- Rewarding innovators who are relentless in their on their vision but flexible on the details of how to get there.

- Fostering a decentralized work culture for new products or services, so that the majority of employees feel like it is expected of them (Amazon’s now famous “two-pizza teams”).

- Third, teaching teams how to experiment their way to innovations.

But once we start talking about government, talk of innovation gets tossed out the door. In fact, the prevailing wisdom among many in the private sector, and likely in the public sector too, is that government is the ultimate death machine to innovation.

Not only does innovation die still-borne in public agencies, government regulations themselves kill innovation in the private sector, many writers and politicians claim ad infinitum.

Do any public agencies have capacity to innovate?

Government still funds innovation and research and development, particularly in defense and health care. But as a culture, government is not the incubator, goes prevailing wisdom. One global survey completed this year puts trust in government around the world below 50%, behind trust in business at about 58%, for its ability to demonstrate change and new leadership.

Public health, as a public endeavor in the United States, is by definition a public undertaking. Thus it remains government-funded, government-run, and thus, be default, the inheritor of government’s best and worst traits.

As someone who has now worked at the international, state, and local levels of government, including in public health, I can attest to government bureaucracies’ failure in many instances to embrace change, inability to stimulate ideas, and poor track record in adopting new ideas to improve how government does business.

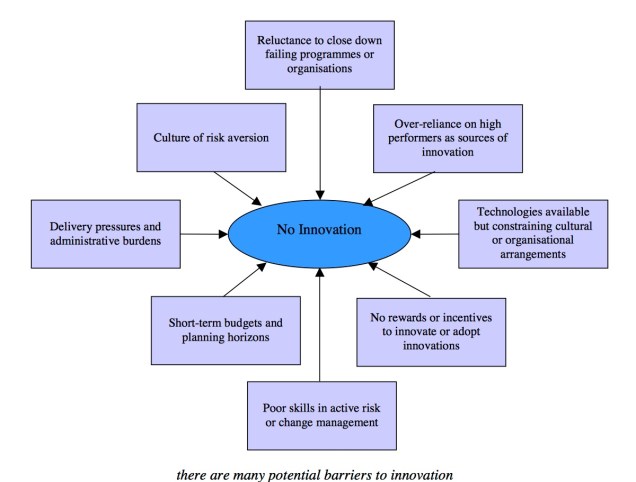

One recent research paper by British researchers Geoff Mulgan and David Albury on the lack of innovation in the public sector noted: “Most service managers and professionals spend the overwhelming proportion of their time dealing with the day-to-day pressures of delivering services, running their organisations [sic] and reporting to senior managers, political leaders, agencies and inspectorates [sic]. They have very little space to think about doing things differently or delivering services in ways which would alleviate the pressures and burdens.” In short, government culture lacks innovation.

The pair argue that innovation should be a core activity of the public sector. They claim this helps public services improve performance and public value, respond better to the public’s needs, boost efficiency, and cut costs.

What are people saying about innovation in public health and health care

In Europe, in 2010, the Association of Schools for Public Health in the European Region’s Task Force on Innovation/Good Practice in Public Health Teaching developed a plan that called for seven action items, two of which focused on innovation:

- Developing more coherence between policies in the fields of education, research and innovation.

- Measures to develop an innovation culture in universities.

Back on this side of the pond, the Harvard Business School held a conference on innovation in the massive health care sector in October 2012, and then published a study in February 2013 on how innovation was seen as critical to health care and health education, which includes public health.

The report found that 59 of the CEOs of the world’s largest and most innovative health-sector organizations most frequently used the word “innovation.” According to the discussion of the attendees, innovation in its broadest sense was even seen as the “only way that change will happen and that creative solutions will be found for our current problems in health care.”

Recent evidence shows that innovation can lead to better outcomes. A 2013 study published in the Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, on technological innovation and its effect on public health in the United States, found a correlation regionally in parts of the country where it was perceived that technological innovation was occurring. The study reported that “relationships between the technological innovation indicators and public health indicators were quantified,” and it was found “that technological innovation and public health share a fairly strong relationship.”

Will innovation remain a dirty word in public health departments at all levels of government?

But does anyone working in a local health jurisdiction, hard-strapped for cash in the post-Great Recession era of downsizing, see innovation taking place in their work environments? As hierarchical bodies, modeled originally after the military since their original inception in the United States, public health bodies are seldom discussed in organizational behavior literature as “innovative.” They are organized hierarchically and often divided by departments with no interchange, and their managers may be unable to allow for information sharing and promote collaboration seen in many for-profit firms.

Yes public health jurisdictions, to win much-coveted accreditation by the national Public Health Accreditation Board, must prove they are committed to quality improvement and a competent workforce. But this by no means is the same as encouraging a culture of innovation to adapt to tremendous change, particularly financial downturns and the challenges posed by chronic disease and the increasing wealth disparity among the top wage earners and the majority at the bottom, which is leading to great health disparities.

One local health jurisdiction that is trying to innovate, the Spokane Regional Health District, developed a strategic plan that calls out as its top two strategic priorities: increasing awareness about the role of public health and securing more stable funding. I think these are spot on and demonstrate how this agency has moved its focus upstream and is adapting itself to succeed in that bruising political arena.

But my own sense of public health jurisdictions, small and large in the Pacific Northwest at least, is that other jurisdictions may not wish to emulate Spokane because of agency rivalries and personal jealousies among upper management. I would love for one day to learn that some of the traits of private sector organizational behavior practices, such as rewarding innovators, promoting a culture of innovation, and teaching workers how to innovate take root. Right now, I’m not seeing that within the sector, and the talk is not matching the walk.