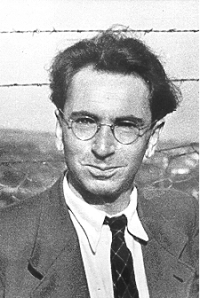

Renowned psychiatrist, philosopher, and writer Viktor Frankl stands as a giant among 20th century thinkers. The Austrian-born Frankl (b. 1905, d. 1997) was a psychiatrist whose life was transformed by his experiences as a Jewish prisoner who survived the Holocaust and internment at the Auschwitz death camp and three other German concentration camps.

With the exception of a sister, all of his immediate and extended family and his beloved wife were murdered by the Nazis. From the aftermath of this horrific experience, he embarked on a life’s work that provided deceptively simple but remarkably clear ideas that literally provide a framework on how all people can live meaningful lives.

Frankl survived his brutal internment, which should have killed him, by seeing a purpose in his ugly reality and by taking control of his responses to that experience with positive actions and a mental attitude that ensured his survival and also his outlook on life and his fellow man and woman. His simple ideas offer no shortcuts, and they uncomfortably place each person in control of how they choose to respond to life’s challenges, even ones as unforgiving as genocide and mass murder.

Frankl proposes all of us are motivated to seek a higher purpose, even when our circumstances are as cruel as a death camp surrounded by barbed wire and vicious men armed with machine guns. Frankl writes: “Man’s search for meaning is the primary motivation in his life not a ‘secondary rationalization’ of instinctual drives. This meaning is unique and specific in that it must and can be fulfilled by him alone… .” More than pleasure, more than material things, meaning motivates us all. It is our purpose for being.

Man’s Search for Meaning, a book that changed modern thinking

Frankl published those principles in his highly acclaimed and influential 1946 memoir, Man’s Search from Meaning, which today has been translated in more than 20 languages and has sold more than 10 million copies. It is considered among the most influential books in the United States, according to a Library of Congress survey.

He originally developed the framework for his sparse set of powerful ideas when he was practicing psychiatry in Vienna before the Nazi occupation and saw how he could help patients overcome their suffering by making them aware of their life’s calling. His treatise, stashed in his coat, was literally lost when he was imprisoned.

Later in his life, when he had achieved global recognition because of the widespread popularity of his bestseller, he was asked by a university student: “…so this is your meaning in life… to help others find meaning in theirs.” His reply was as clear and direct as the theory behind his therapy, “That was it, exactly. Those are the very words I had written.”

As one writer influenced by Frankl, Genrich Krasko, points out, Frankl’s ideas are more prescient today, given millions have no meaning in their lives, particularly in affluent societies: “Viktor Frankl did not consider himself a prophet. But how else but prophetic would one call Frankl’s greatest accomplishment: over 50 years ago he identified the societal sickness that already then was haunting the world, and now has become pandemic? This ‘sickness’ is the loss of meaning in people’s lives.”

Logotherapy, Frankl’s foundational theory

Frankl called his system logotherapy, derived from the Greek word “logos,” or “meaning.” It has been called existential analysis, which may over-simplify its scope. The philosophy and medical practice boils down to providing treatment through the search for meaning in one’s life. Its utterly basic but ultimately powerful foundational ideas are easily summarized:

- Life has meaning in all circumstances, even terrible ones.

- Our primary motivation in living is finding our meaning in life.

- We find our meaning in what we do, what we experience, and in our actions we choose to take when faced with a situation of unchangeable suffering.

Frankl notes, “Most important is the third avenue to meaning in life: even the helpless victim of a hopeless situation facing a fate he cannot change, may rise above himself, may grow beyond himself, and by so doing change himself. He may turn a personal tragedy into triumph.” This latter point is particularly poignant, as it calls out the role that adversity can have in shaping us and our destinies and improving our character and our life’s narrative.

In short, no matter what circumstances we find ourselves, so long as we have a purpose, we can find fulfillment. What’s more, we are fulfilled by right action and by “doing,” not through short-term pleasure or narcissistic pursuits.

Frankl argues that meaning can be found in meaningful, loving relationships, in addition to finding it through purposeful work or deeds. In fact, it was the strong love of his first wife that kept him alive amid the unspeakable horrors of Auschwitz. He felt her presence in his heart and it literally let him live when others around him perished.

Frankl’s core ideas at odds with more ‘accepted’ health and mental health paradigms

Frankl’s ideas collide with behaviorist models, which show that conditioning will determine one’s responses—the proverbial Pavlovian dog or Skinnerian lab rat. By contrast, through his own experiences and those he observed treating depressed and suicidal patients before and after the war in Vienna, Frankl claims that “everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.”

When faced with a situation, we all chose. But our power is defined by our actions. “Between stimulus and response, there is a space,” he claims. “In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

The concept of personal choice conflicts with extensive research that clearly documents how one’s environment, race, socioeconomic status, and more—the so-called social determinants of health (SDOHs)—shape one’s life more than one’s individualistic decisions.

For two years, while earning my MPH at the University of Washington School of Public Health from 2010 to 2012, I found myself frequently and painfully at odds with current research and literally thousands of studies that proved to me that SDOHs will impact our lives in the most profound ways.

Yet I found the field and its most ardent practitioners lacking an explanation that showed the real power people have in controlling their personal outcomes. This is something that the public health field and my faculty sharply criticized by showing the medical model, which tells persons to control their health, has largely failed to promote wider population health metrics.

While I do embrace a “policy and systems” approach, I even more strongly believe that every person has the ability to make life-changing choices, every minute of every day—from the food they put in their mouth, to devices they watch daily, to the people they associate with, to the jobs they take or do not take (however awful often), to the way they manage their personal emotions. They have choices, and often they are cruel and brutally unfair choices, which often favor the privileged.

Frankl was famous for meeting with some patients, asking them to reflect on finding meaning in their lives over their entire life span, and providing the mental treatment they needed to take control of their lives without future interventions or drugs, which predominates the American model of mental health treatment. Some of his patients only required one session, and they could resolve to deal with life’s circumstances without any further intervention.

This is a radically and in fact dangerous model that challenges how the United States is grappling with mental illness nationally, though many practitioners use Frankl in their work. One psychiatrist I tweeted with wrote me back saying, “I’m far from the only one [using Frankl]! There’s a large humanistic community in the counselling/psychotherapy world.”

Frankl’s ideas continue to be studied, refuted, debated, and argued by learned and well-intentioned academics, which I think would amuse Frankl. He was more interested in the practical work of day-to-day living and less with becoming the subject of a cult following.

As one commentator I saw in a documentary who knew Frankl noted, Frankl was not interested in fame, otherwise he would be more famous today.

Here is just one example showing how theorists explain logotheraphy; see the table by Paul Wong on life fulfillment and having an ideal life.

Why Frankl’s thinking profoundly inspired me and thousands of others

For more than three decades, I have been wrestling with the concept of personal responsibility and the influence of our environment and systems that impact our destinies. Such factors include one’s family, country, religion, income, the ecosystem, our diet, and political and economic forces, among others.

I also have been fascinated by examples of people choosing hard paths in dire circumstances as the metaphor that defines successful individuals’ life narratives. In Frankl’s death camp reality, this ultimately boiled down to choosing to be good, and helping fellow prisoners, or choosing to partake in evil, which many prisoners did as brutal prisoner guards called kapos.

No one gets a free pass in this model, and all people in all groups can be one or the other, Frankl says. “In the concentration camps, for example, in this living laboratory and on this testing ground, we watched and witnessed some of our comrades behave like swine while others behaved like saints,” writes Frankl. “Man has both potentialities within himself; which one is actualized depends on decisions but not on conditions.”

I had not been able to order these two lines of thinking into a coherent set of principles, as Frankl so perfectly did. When I stumbled on him quite by accident or maybe design this summer, while reading books by Robert Greene and even management guru Stephen Covey, I had that most rewarding and delicious feeling of “aha.” It was more like, “Wow, what the hell was that!”

It felt like a thunderclap. I almost reeled from the sensation. I then began to tell every single person I know about Frankl, and I learned many of my colleagues had already read him. I felt robbed not one teacher or academic, at three respected universities I attended, had covered or even mentioned Frankl, when his ideas are foundational to our understanding of the fields of psychology, public health, business, organizational behavior, religion, and the humanities in the 21st century.

Frankl deserves vastly more attention then he is given by health, mental health, and social activist thinkers. That is a shame too, because as a speaker, Frankl brimmed with enthusiasm and could convey complex ideas in the simplest ways to reach his audience. Watch his presentation at the University of Toronto–a brilliant performance.

Frankl’s ideas matter to each of us, in everyday life

One my most satisfying feelings is discovering that one’s personal life experiences and ideas on issues as big as the meaning of life also resonate profoundly with millions of others—those who have read his work. Even more gratifying is discovering that the core principles to living life amid hard choices can be grounded in principles that can help everyone, even in the most dire of personal experiences.

My own travels in the developing world stand out for me. I met countless people facing vastly more painful, difficult, challenging lives than I have faced. Yet, the wonderful people I met had nothing but smiles and treated me with genuine sincerity. I had to ask myself, why is it that so many people are clearly content when their surroundings indicate they should be experiencing utter despair and even violent rage. Why is there kindness in their hearts and peace with their reality.

I understood at all levels what I was experiencing. But Frankl’s framework ties this rich set of personal experiences to all of us, and to larger existential ideas of what we are meant to do with our time.

For Frankl, the answer is just doing what life needs us to do. As Frankl wrote nearly 70 years ago, “Life ultimately means taking responsibility to find the right answer to its problems and to fulfill the task which it constantly sets for each individual.”

With that point, I now must ask you, the reader, What are you doing with your life, and are you doing what you are being asked to do? You cannot escape this question, and if you avoid it, you will always have the pain and emptiness of not listening to your own calling. The choice of course is your own.