(Ed. Note: Dozens of links are provided below, after the introduction.)

Detroit’s unwanted celebrity status nationally and internationally continues to fascinate me. Detroit is now known as a failed American urban experiment. For the more cynical or the painful realists, it represents the dark end to America’s middle-class dream, and the embodiment of the decline of American power and even its civilization.

Detroit rose like a phoenix at the beginning of the 20th century and then experienced the near death of the American automobile industry at the start of the next one, culminating in the taxpayer-funded bailouts of General Motors and Chrysler during the Great Recession. Once the nation’s fourth largest city, the population has fallen from 1.8 million to less than 800,000 in 50 painful years.

Since the violent Detroit riots of 1967 that killed 43 and burned more than 1,000 buildings, the community has transformed into a nearly all-African-American city. Sadly, it now ranks as the country’s murder and arson capital. Multiple factors, well beyond Detroit’s control, spurred these changes. These include white flight and suburbanization, along with national racial politics and globalization.

From a public health perspective, there are not many major cities doing worse. Entire neighborhoods have been vacated. Burnt out shells of homes and businesses dot the urban landscape that now is turning to seed. Nearly half of the city’s children live in poverty. Once glorious buildings that were testament to the confidence in industrial capitalism, notably the ghostly Michigan Central Station, stand vacant as monuments to a past glory. They are our America’s modern-day Roman Colosseum, symbol of a dying or dead empire.

Detroit is also my home town, where some of my family have long roots as Michiganders. It is the place where my life story began, at the intersection of two stories of my adoptive and biological families, who all eventually fled or simply moved away.

To help others understand Detroit Motor City and why it matters, now more than ever, I have compiled some of my favorite links to resources, films, books, and online content that I have uncovered recently. Take a moment to learn more about this famous place that once was the world’s greatest industrial city.

Detroit, Enduring Icon of Decline and “Ruin Porn” Celebrity

- Detroit Disassembled, photo book by photographer Andrew Moore (highly recommend)

- The Ruins of Detroit, photo book by Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre (highly recommend)

- James Griffioen, Detroit photographer of decay (recommend)

- Five Factories and Ruins (web site)

- Lost Detroit: Stories Behind the Motor City’s Majestic Ruins, by Dan Austin and Sean Doerr, provides historic and architectural background

- American Ruins and The New American Ghetto, by Camilo José Vergara, depict dereliction and abandonment in cities like Detroit, Camden, N.J., and Chicago

- Julia Reyes Taubman, socialite ruin photographer of Detroit and subject of some blowback for photographing decay while protected by a wall of money

- Detroit 138 Square Miles, website that accompanies photographer Julia Reyes Taubman’s photo book

- Beautiful Terrible Ruins, art historian Dora Apel examines ways Detroit has become the paradigmatic city of ruins, via images, disaster films and more and notes that the images fail to show actual drivers in the downward spiral, such as globalization, neoliberalism, and urban disinvestment

- Diehard Detroit, a time lapse video of many of Detroit’s famed architectural ruins, abandoned factories and homes, monuments, buildings, and freeways, with absolutely no perspective on the meaning behind the mayheim, just titilating entertainment with great technique and a cool drone toy (it is stunning visually, and thus classic “ruin porn”)

- Detroit’s Stunning Architectural Ruins, and Why Documenting Its Faded Glory Matters (an article by the Huffington Post, a liberal blog which exploits unpaid “contributors” more than Henry Ford ever did his factory workers)

- Urban Ghost Media, photos of the much-photographed and now infamous Eastown Theater

Detroit and Media Coverage

- How Detroit Went Broke, an in-depth investigation by the Detroit Free Press of Detroit’s 50-year history prior to its historic bankruptcy declaration, including unsustainable borrowing, population decline, pension mismanagement, tax shortfalls, state failures, and leadership failures particularly of former indicted Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick

- Five years of foreclosures as shown by an investigation of the Detroit Free Press–a vast sea of distressed properties and ruined dreams

- Motor City MuckRacker, an independent and progressive blog that provides daily coverage of news in Detroit (follow its Twitter account)

- Detroit, Infamous Arson Capital of America (from 2015)

- Murder City USA, the stats on crime in Detroit as of 2014

- Let Syrians Settle Detroit, a guest column in the New York Times that examines GOP Gov. Rick Snyder’s call to resettle up to 50,000 immigrants in Detroit, some being displaced Syrians

- Why the Media Don’t Get Detroit—and Why It Matters, a February 2015 article in the Columbian Journalism Review

- Detroit’s Transition from having the best to worst mass transit

- Maude Barlow, a prominent left-leaning Canadian intellectual, criticizes Detroit’s management of basic water services (but what should the city do when it is broke?)

- Story on a reality TV show being filmed in Detroit linked to a young girl’s death, highlighted in Charlie LeDuff’s book on Detroit and revealing Detroit’s emerging status as a reality TV colonial territory

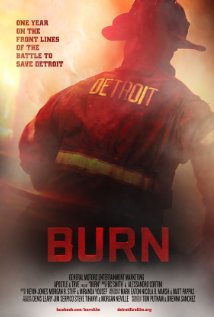

Must-See Detroit Documentary Film: Burn

- Burn, a documentary film by Tom Putman and Brenna Sanchez, tells a year-long story of the year in the life of Detroit firefighters, who battle uncontrolled arson against all odds (amazing filmmaking!!! … from the firefighters interviewed: “That is how you burn a city down. One at a time.”)

- Interview with filmmakers Putnam and Sanchez on their documentary Burn (great read on scrappy filmmaking with a purpose)

- The Making of Burn—so, you want to make a great film no one in power gives a crap about, but you have to do it anyway

Must-Read Books on Contemporary Detroit

- Detroit, an American Autopsy, by iconoclastic Detroit gonzo journalist Charlie LeDuff, who stretches the truth to tell a good tale

- Detroit City Is the Place to Be, Mark Binelli’s nuanced and anecdote-rich account of a journalist returning to his hometown

- The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit, by Thomas Sugrue, details Detroit’s twentieth-century history (for the wonks)

- Say Nice Things About Detroit, a novel about a former Detroiter who returns home after 25 years (have not read this, but you get the idea from the title)

Detroit, The Former Glory

- Ford Motor Co. film on Detroit, a stunning piece of corporate propaganda

- Detroit: City on the Move (1965), a propaganda film as part of its bid to host the 1968 summer Olympics (famous line about the Motor City: “a master plan of urban efficiency”)

- Albert Kahn’s 400 buildings in Detroit, a celebration of Detroit’s most celebrated architect, who designed everything from the Packard plant to civic buildings to mansions

Pro-Detroit Media Coverage and the “Re-Birth” Branding

- Opportunity Detroit, the city’s official redevelopment propaganda website

- Profile of the Head of the Firm GalaxE, a businessman notorious for outsourcing and insourcing

- Outsource to Detroit, coverage of the campaign that promotes Detroit as a cheaper alternative to developing nations, a virtual Third World in America

- Company profile of the advertising firm that came up with “Outsource to Detroit” campaign

- The Detroit Industry fresco series/murals by famed Mexican artist Diego Rivera at the Detroit Institute of Arts, tells the story of Detroit as only Rivera can

- Why the Ford River Rouge Factory Matters

- Charles Sheeler, photographer of the Rouge Plant (the plant is in neighboring Dearborn)

- Photographs of photographer and artist Charles Sheeler

- The Work of Charles Sheeler

Nice Photo Essays of Before and Now:

- The Detroit of Herman Krieger, a nice set of photo essays on the former and current Detroit of a former resident, showing the places now razed or changed

- Faded Detroit Blog

- Forgotten Detroit

Detroit Stories and Research of Interest

- Urban Gardens of the 1890s: Progressive Mayor Hazen Pingree’s urban gardens launched the national urban garden movement in the 1890s

- Report on Opportunities for the Detroit Food System, funded by Kellog Foundation, looking at food issues in Detroit today